At this year’s DRG Forum in Berlin, there was widespread agreement that the DRG system is in need of comprehensive reform. There is no shortage of sensible proposals, such as the introduction of cross-sectoral remuneration by means of hybrid DRGs or a stronger consideration of maintenance costs in hospital financing. Nevertheless, some speakers were skeptical, as changes in the past have in some cases been only moderately successful. Consider, for example, care cost carve-outs, which have so far burdened rather than supported many hospitals. [1]

If further far-reaching changes are now to be made to the hospital reimbursement system, it is worth taking a look at the past. This involves the question of what changes have occurred in inpatient service provision since the introduction of the DRG system a good two decades ago.

Could DRGs reduce inpatient length of stay?

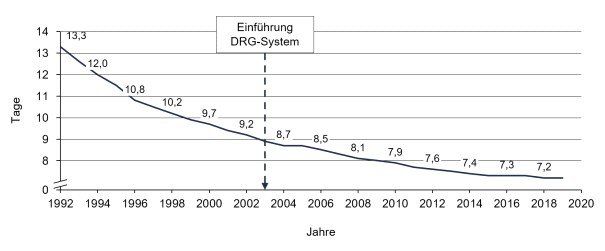

One of the central goals of the introduction of flat rates per case in Germany was to shorten the average length of stay in hospital. Since each case of treatment is reimbursed at a flat rate, there is an incentive to keep the length of stay as short as possible, or so the assumption goes. In fact, such an effect can be observed in various areas after the introduction of DRGs. For example, Feess et al. (2019) show that after the replacement of per diem care rates, older patients (> 65 years) in particular were discharged earlier. Smaller hospitals were able to reduce their lengths of stay more than larger institutions. [2]

Figure 1 suggests that these effects have also occurred at the system level, as the average inpatient length of stay has continuously decreased since 2003. However, this development started long before the introduction of the DRG system. A recent study by Messerle and Schreyögg (2022) could not find any evidence that the observable reductions in length of stay after 2003 can be attributed to the new payment system. [4]

A similar picture emerges in other countries. In the Swiss reimbursement system, which is closely related to the German system, Busato and Below (2010) concluded that the decline in average length of stay could only be attributed to the introduction of the DRG system to a limited extent. [5] If outpatientization continues to gain momentum, a rebound in length of stay could even be observed in Germany in the future, as the average case severity of inpatient cases will increase.

Has the DRG system led to higher case numbers?

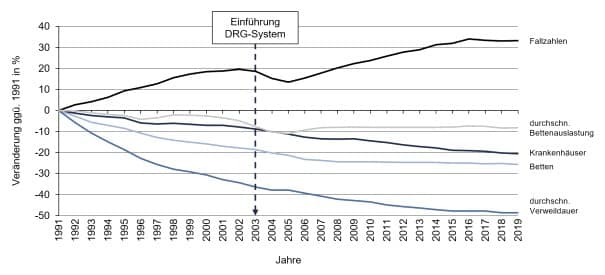

In addition, flat rates per case provide an incentive to provide as many cases as possible, provided that the contribution margin is positive. Current study results indicate that the introduction of the DRG system in Germany has indeed led to an expansion of volumes in the inpatient sector. Messerle and Schreyögg (2022), for example, observe an annual growth in service volumes of 2 percent, which is directly attributable to the DRG system and not to other effects (demographic development, medical-technical progress, etc.). This corresponds roughly to an increase in hospital costs of more than one billion euros per year. [4]

These developments are favored by existing structures. Compared to other OECD countries, Germany has significantly higher bed capacities. Last year, 791 beds were available per 100,000 inhabitants. The Netherlands and Italy need only 308 and 295 beds, respectively, to care for the same number of inhabitants. [6] Since existing capacities are often also used (“a hospital bed built is a filled bed” [7]), there is a danger that an incentive has arisen in certain service areas to increase the number of cases beyond what is necessary. [8]

Can the compensation system be improved?

A reform of the inpatient remuneration system must go beyond merely correcting the symptoms and address the causes. This includes, among other things, breaking the strong link between service volumes and remuneration and focusing more on regional care needs and the quality of the services provided. The Corona pandemic has also made it clear once again that a further increase in the number of cases is hardly realistic in the future. This development had already begun to emerge in 2016 (see Figure 2).

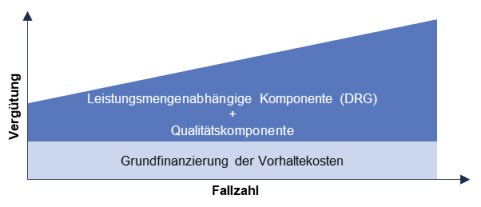

A three-tiered reimbursement structure is currently frequently discussed. This includes a basic financing of the maintenance costs that is independent of the service volume and depends on the level of care, a component that is dependent on the service volume, as in the current DRG system, and a quality component that takes into account the quality of treatment per case. [9] The question of which cases should actually be treated in the hospital should also be considered. A first step toward cross-sectoral care could be hybrid DRGs, which reimburse services at the same level regardless of whether they are performed in an outpatient or inpatient setting.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to say reliably when changes can be expected at present, since the legislature is still very busy dealing with the pandemic. It is also unlikely that health insurers will provide comprehensive start-up financing for the new reimbursement structures due to their increasingly deteriorating financial situation.

Conclusion

It should be noted that the DRG system has not been able to deliver on all its promises over the past 20 years. Among the positive developments are the incentive for greater efficiency and greater transparency in the provision of services. At the same time, the introduction of DRGs has not further accelerated the reduction in length of stay. The volume of services, on the other hand, has increased, in some areas probably beyond what is necessary. There is thus a need for change in inpatient remuneration, and developments in the direction of greater consideration of quality and retention costs are desirable. However, it is increasingly unlikely that such far-reaching reforms will be initiated or even implemented during this legislative period.

Literature list

| [1] | M. Heumann und J. Kühn, „Entgeltverhandlungen 2022: Die große Ratlosigkeit“, f&w, Nr. 3, S. 251-255, 2022. |

| [2] | E. Feess, H. Müller und A. Wohlschlegl, „Reimbursement schemes for hospitals: the impact“, Applied Economics, Bd. 51, Nr. 15, S. 1647-1665, 2019. |

| [3] | Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), „Gesundheit. Grunddaten der Krankenhäuser,“ Wiesbaden, 2022. |

| [4] | R. Messerle und J. Schreyögg, „System-wide Effects of Hospital Payment Scheme Reforms: The German Introduction of Diagnosis-Related Groups“, Hamburg Center for Health Economics, Hamburg, 2022. |

| [5] | A. Busato und G. von Below, „The implementation of DRG-based hospital reimbursement in Switzerland: A population-based perspective“, Health Research Policy and Systems, Bd. 8, Nr. 31, 2010. |

| [6] | OECD, „Health at a Glance 2021: OECD Indicators“, OECD Publishing, Paris, 2021. |

| [7] | M. Shain und M. I. Roemer, „Hospital costs relate to the supply of beds“, Modern Hospital, Bd. 92, Nr. 4, S. 71-73, 1959. |

| [8] | R. Milstein und J. Schreyögg, „Empirische Evidenz zu den Wirkungen der Einführung des G-DRG-Systems“, in Krankenhaus-Report 2020, J. Klauber, M. Geraedts, J. Friedrich, J. Wasem und A. Beivers, Hrsg., Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020. |

| [9] | KU Podcast, „Finanzierung im KU Podcast mit Herrn Dr. Florian Kaiser“, 2022. [Online]. Verfügbar: https://ku-gesundheitsmanagement.de/aktuelle-folge/. [Zugriff am 30.03.2022]. |